Opportunities for relatives to visit from Gaza are the rarest of pleasures – even if they’re often shrouded in sorrow. My kids met their aunt.

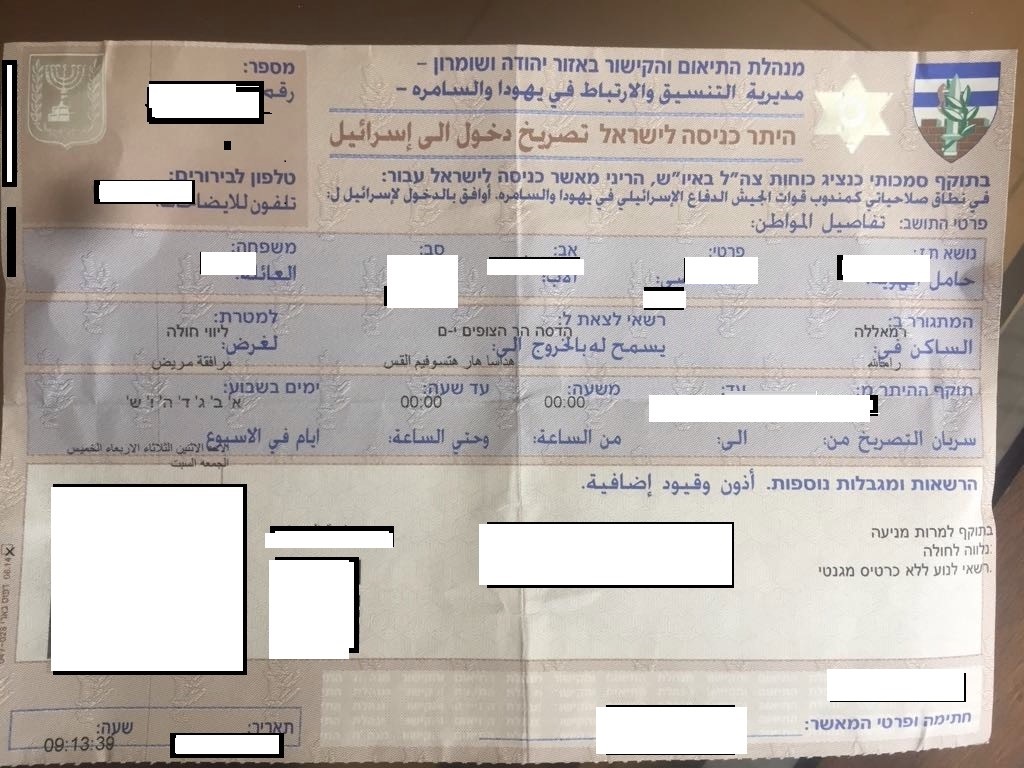

In 2012, the Israeli restrictions on Palestinians traveling between the West Bank and Gaza were “looser”, and my partner Osama was able to get a permit to visit Gaza, following the death of his eldest sister. That was his first visit in 16 years. Osama was born in the Gaza Strip, and his mother and three surviving siblings still live there. For them and for many families from Gaza, the sorrow over illness and death is mixed with joy for the rare chance to reunite with loved ones. The travel restrictions have gotten tighter since 2012, and passage between Gaza and the West Bank is now mostly limited to urgent medical cases. Osama’s family lives in the Jabalia Refugee Camp, a hundred kilometers from Ramallah, but the travel restrictions push it further away, approximately to the other side of the moon.

But this month we got good news, if one considers treatment for a cancer patient in a hospital in Hebron to be a happy occasion: Shirin, Osama’s surviving sister, suddenly announced that she would arrive the following day, to accompany her sick friend, who received a permit from the Israeli authorities to reach Hebron. Shirin called Osama by video from their mother’s apartment, and it was hard to hear her over the laughter, loud conversations and crying children.

“Gaza,” Osama said as he hung up the phone, and the frustration in his voice was mixed with affection. “Every day is a party.”

At night, Shirin called back and explained: her friend, the cancer patient, couldn’t get a permit for one of her children to accompany her, because of the Israeli Shin Bet’s policy not to allow young adults to leave Gaza. Shirin, 54, was the substitute. I asked Osama if he would travel to the hospital in Hebron to meet his sister there.

“No, no, she’ll come straight here,” he said.

“And her sick friend?”

“Shirin says she’s strong. She’ll go to the hospital alone.”

The next day, Osama collected Shirin from the public taxi station and brought her to our apartment. She was short, round, and dressed in a long traditional coat. The hijab, mask and glasses couldn’t hide the resemblance to her mother, whom I had met ten years ago, when she came to the West Bank to accompany her eldest daughter for medical treatment in Ramallah, a few months before the daughter passed away. I walked toward Shirin, stopped, and then pounced on her.

“There is no coronavirus,” I declared and hugged her tightly. It took our children, 3-year old Adam and 6-year old Forat, about two minutes to become entranced by her. They had never met a member of Osama’s family. They demanded that she sit next to them, play with them and hear all about their preschool and school. After about an hour, Shirin wanted to pray, and Osama gave her the prayer rug that we had found in the closet when we moved into the apartment. At the time, I had asked Osama why he wanted to keep it, and he explained: “In case my mother ever comes to visit.”

Shirin donned her hijab again, laid out the rug, knelt and began murmuring the prayer. Forat and Adam watched, fascinated.

“What are you doing?” Adam asked her, his eyes wide. I told him she was praying and asked him not to disturb her. He ignored me and repeated the question. She didn’t answer but rather continued bowing and straightening her torso in a kneeled position, according to the rhythm of the prayer. Adam’s smile widened. The next time she lifted her forehead from the rug and straightened her torso, Adam jumped onto the rug and perched close to her knees, his head tilted upward, anticipating her next descent. She bowed her head again, eyes closed in concentration, and her forehead collided with Adam’s forehead. Both of them burst into laughter.

“Now your mother will have proof that you don’t pray,” I told Osama, because it was obvious that Forat and Adam had never seen Muslim prayers up close.

The gaps between Shirin’s life in Gaza and Osama’s life in Ramallah/al-Bireh became apparent. During the first few days of her visit, around noon, Shirin would ask me if I had finished working yet, because the women in her family who work outside the home – do so part-time, to avoid disrupting their housekeeping and childcare responsibilities. The high prices at the supermarket surprised her. Osama told me that her daughter who, like me, is a lawyer, earns 700 NIS ($210 U.S.) per month in her law firm job, working five days a week, five hours each day. Osama’s family is lucky: Some of them were public servants for the Fatah-led Palestinian Authority, and they still get partial salaries. All five of Shirin’s sons and daughters – like the children of Osama’s eldest brother – completed university degrees. But there are no jobs in Gaza.

In the morning, when Forat screamed that Osama was messing up her hair, Shirin laughed and kissed Forat’s cheek. “By the volume of her voice, I can tell she’s part of our family”.

At night, after the children slept, Osama and Shirin would sit around the kitchen table, snacking from plates of peanuts, sweet lupine and cucumber slices. She told him of her decision to leave her house and move into a rented apartment: She wasn’t getting along with her daughter-in-law, who lived with her in the building that belonged to her late husband’s family.

“How does it feel to see Shirin?” I asked Osama.

“I don’t know,” he answered. I wondered if he was thinking of his mother, who is 80 years old. A few weeks earlier, I had found him sitting stony-faced after finishing a phone call with his mother. I had asked him about his mother’s health, and he immediately understood what I meant.

“No, Madam Lawyer,” he told me. “Fortunately and unfortunately, my mother is not eligible for a travel permit to the West Bank.”

Shirin finally joined her friend in Hebron and then brought her back to our apartment. The week ended quickly. I drove Shirin and her friend to the Qalandia checkpoint, from which a minibus would take them directly to the Erez checkpoint between Gaza and Israel. I felt a rush of empathy for Osama, who maintained his refusal to tell me how he felt about her visit. I watched Shirin disappear into the entrance of the checkpoint, on her way to the other side of the moon.

This post was also published at haaretz.com on November 30, 2020: