For the first time after two months of corona-closure, we were leaving the West Bank to visit close friends in the Israeli city of Holon.

“Forat, brush your teeth so that we can leave,” I begged. Her brother Adam looked at me with a grin and began to run, a sign that he wanted me to chase him.

“You also have to brush your teeth,” I said and ran after him. He squealed with giggles, until I caught him and brought him to the bathroom.

“Lone!” he yelled in Hebrew. Alone. I gave him the toothbrush. He sucked the toothpaste from the brush and swallowed it, smacking his lips.

“Now it’s Ima’s turn,” I said. I wedged the toothbrush into his mouth. He tried to scream while simultaneously clenching his teeth.

“I want to wear the ice cream cone dress,” Forat said. As part of our corona routine, in which every day resembles the previous one, Forat puts on the same dress every morning, which used to be white with pictures of ice cream.

“Sweetheart, today we are leaving the house. You need to wear something clean and not torn.”

“Izi maaneh?” Adam asked.

It was too early in the morning to decipher the speech of a two-and-a-half year old child who speaks three languages. “What, my sweet?” I asked him.

“Izi maaneh?” Adam asked again. Forat translated: “He wants to know if Baba is coming with us,” she said. Yiji maaneh means “will come with us”, in Arabic.

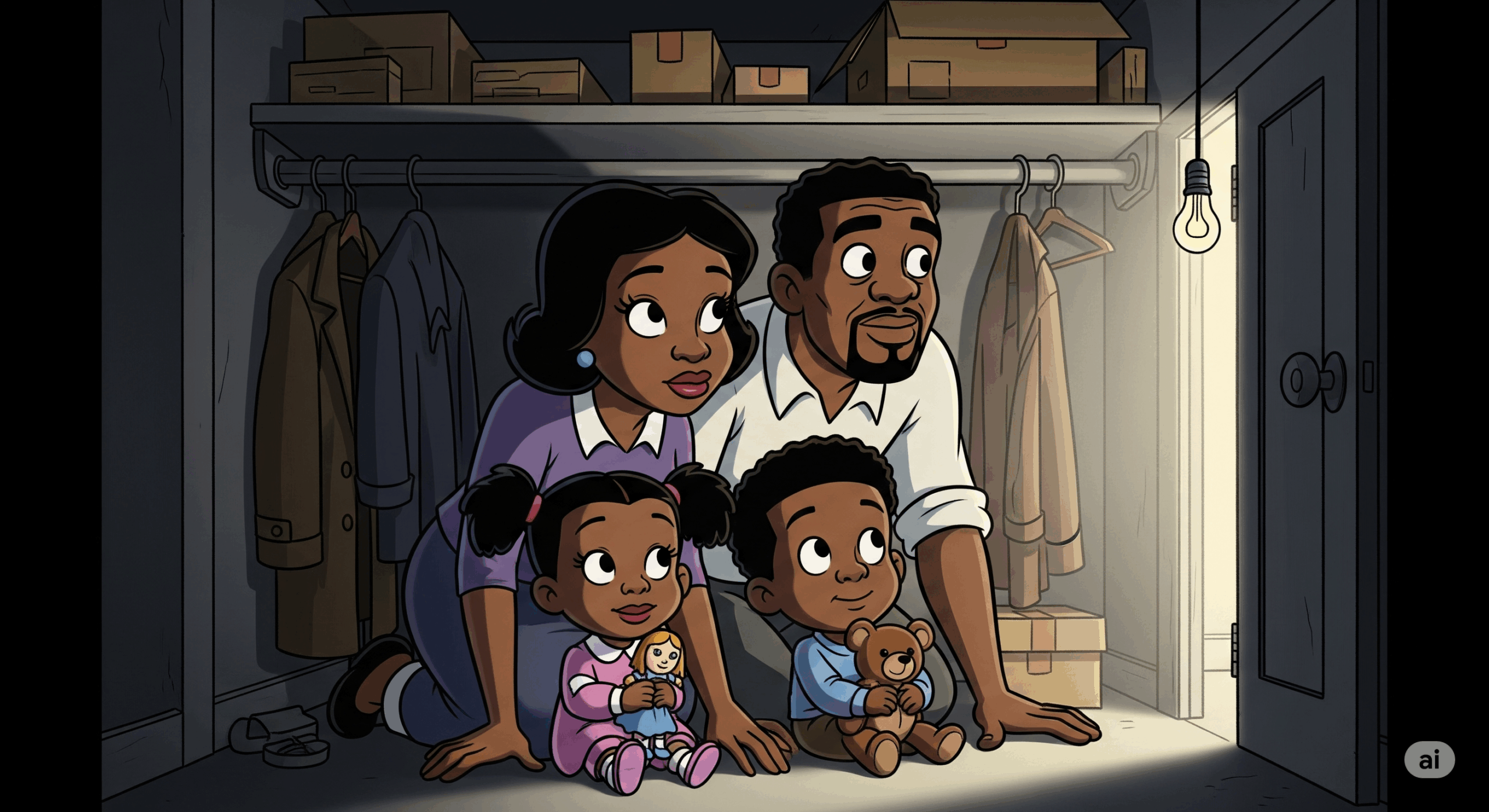

Forat answered him: “No, Baba won’t come with us because of those bad guys.” It took me a second to realize she meant the soldiers at the checkpoints who allow Israelis but not Palestinians, like her father, to cross.

“Do you mean the soldiers?” I asked her.

“Yes. They’re bad guys but not bad like the bandits in Morphle and Mila,” she said, referring to the characters in the cartoon she watches in the afternoons, while I put Adam to sleep. “The bad guys in Morphle and Mila steal the children’s toys, and Officer Freeze has to lock them in a cage.”

From the time she began to ask, I had always told Forat that the people who stand at West Bank checkpoints have trouble sharing, and that’s why they let Israelis but not Palestinians cross. I considered initiating a conversation about it but remembered her incredible ability to perceive what happens around her and come to independent conclusions, which evolve as she receives new information and matures. I decided to continue to listen to how she understands her world, now that Israelis and Palestinians can travel again, but not to the same places.

For the first time in two months, we were leaving Ramallah, to visit Michael, a close friend from the Israeli city of Holon, his five-year-old daughter Noa and his three-year-old son Itamar. West Bank schools are still closed, and we have no child care on the horizon, but as of early May, the Palestinian police have begun allowing travel into and out of the cities. They still impose a nightly curfew in the twenty percent of the West Bank in which they are allowed to operate, trying to prevent the large gatherings customary for the Muslim holy month of Ramadan.

I drove with the children to the road that is shared by Palestinians and Israeli settlers, and I saw the red roofed homes of the settlements. I reached the checkpoint that separates the Palestinian village of Naalin from the Israeli settlement of Modiin Ilit, a checkpoint that Palestinians, including Forat’s father, are not allowed to cross. When I travel to Israel or to the parts of the West Bank beyond the checkpoints, I travel with the children alone.

“Good morning,” I said with a smile to the woman whom Forat would consider to be the on-duty Bad Guy, a young security guard from the private security company running the checkpoint.

“Good morning.” She returned my smile and opened the gate. I stopped at the Shilat junction to buy the groceries that had run out during the closure: tofu, organic ketchup for the children, kosher chicken. The grocery store was bursting with people, despite signs ordering shoppers to maintain a two-meter distance. In the crowded rice and legumes aisle, a large woman inadvertently pushed me, and I found myself pressed up against the paunch of an older man, wearing a yarmulke, with a pistol tucked into the waistband of his pants. I wondered when Forat would start to notice the existence of armed settlers, and how I would answer her questions about them. What would Morphle and Mila say?

The visit to Holon was healing, after weeks in which Forat and Adam hadn’t played with any other children. The playgrounds in Ramallah are still closed, but the playground in Holon was open and, except for the mask-wearing – felt wonderfully normal. Adam ran from the swings to the see-saw and back again, and Forat dragged Noa to the slide, where an imaginary hamster was sick with a life-threatening illness that could only be cured by the magic of two fairy-queens. Again I was struck by how naturally Forat speaks to other children in Hebrew.

“Yesh dog honaka!” Adam screamed in joy. Yesh=There is. Dog=dog. Honaka=there. Michael, who understands English and Arabic, laughed and led Adam to pet the dog.

When it was time to leave, Forat asked if Noa could come home with us.

“Not today,” I said. Michael actually visits us in the West Bank, but he doesn’t allow his children to come.

I reached the outskirts of Ramallah around 7 pm. Palestinian police stood at the entrance but did not yet block people from entering. There was heavy and dangerous traffic on the streets, hungry drivers rushing to their break-fast meals. Osama came out of our apartment to help me with the children and the groceries. We sat in our garden and ate the molochia (mallow leaves with tomato and onion) and rice that Osama had prepared. Neighbors sat above us on their balconies, eating and talking in the dusk.

“Ima, can I also go back to kindergarten, like Noa?” Forat asked.

“Not yet, sweetheart,” I said. My heart went out to her, a child who loves people so much, closed up in the house for the last two and a half months.

Uncharacteristically, Forat answered me in a soft voice: “I want the virus to end, Ima,” she said.

“Me too,” I told her.

This post was also published at haaretz.com on May 20, 2020:

https://www.haaretz.com/middle-east-news/leaving-the-west-bank-for-a-foray-into-israel-1.8856949

Раньше я думал иначе, благодарю за информацию.

——-

sosamba-138 | https://sosamba-138.ru/