The first time I heard my daughter refer to herself as Jewish was when an Israeli soldier prevented us from traveling, thinking we were Palestinian

We had been in the new house a week and a half, and I still hadn’t managed to buy a bed for Forat, clothes hangers or a car. But on Friday morning I borrowed a friend’s car and took the children for a day trip to Tel Aviv. Our first stop: the unveiling ceremony for my uncle, who died two months after we reached the United States. Exactly one year ago, I was busy organizing our new apartment in Philadelphia when my father called to tell me of the death his eldest brother, Shafiq.

Again I fought with Forat in an unsuccessful attempt to leave the house on time. Again I yelled and threatened her, that there wouldn’t be time to play with her friend Noa, who lives in Holon and who was the third and last planned stop on our trip, after the unveiling and a visit to a Tel Aviv friend’s storage space to collect a set of toy chests. Forat stood in the doorway of the apartment screaming, “Pinukki the Bear is angry at you! I’m never going to do clean-up-tidy-up again!” Great. She’s learning from me how to make threats.

Osama walked us to the car and buckled the children into their car seats while I arranged our provisions for the trip on the seat beside me – water, sandwiches, fruit and “healthy chocolate” balls. We drove west, toward the town of Beitunia and the villages of Ein Arik and Dir Ibzi’, from which we would drive to Modiin and then Tel Aviv.

By the time we reached Dir Ibzi’, Adam and Forat had devoured eight healthy chocolate balls, six melted cheese sandwich quarters and a peach and a half. Adam fell asleep. The food revived Forat, who began peppering me with questions.

“Ima, is there something that there isn’t in Philadelphia but there is everywhere else in the world?” I thought the question stemmed from the things she was re-discovering here, things she forgot during our stay in the U.S., like humus and falafel from the neighborhood restaurant, okra, sahleb and za’atar with olive oil.

“That’s a good question,” I said. “Do you have ideas of what it could be?”

“No, I want you to answer me.” She spoke the last sentence half in English, half in Hebrew. As was the case the last time we returned to Palestine, the exodus from an English-speaking country encouraged her to turn Hebrew from a passive language (listening to me) to an active one: Ani rotza she-at to answer me.

“Maybe – longing for Philadelphia?”

We turned down the steep, winding street that leads from Dir Ibzi’ to the main road. It was a stunning view of sky, clouds, and green plants scattered on agricultural terraces among brown soil and white rocks. We approached the T junction at the bottom, where Palestinian drivers reach the main road, used by both settlers and Palestinians, stretching west toward the checkpoint between the Palestinian village of Naalin and the Israeli settlement of Modiin Ilit.

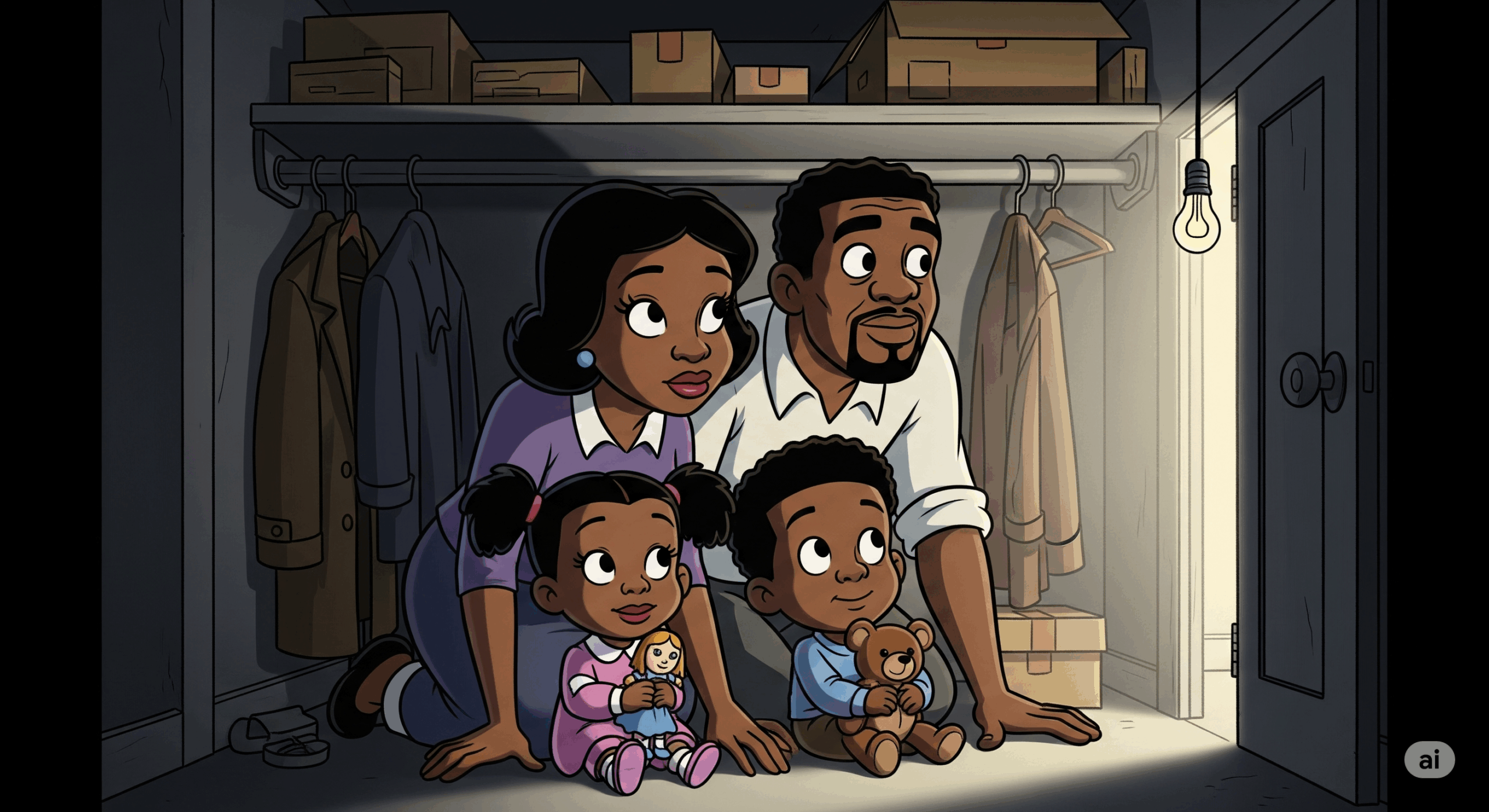

The yellow iron gate was closed. Two soldiers stood before us, in front of a parked army jeep. I remembered the attack that had taken place the week before, at the spring near Dir Ibzi’ and the Israeli settlement of Dolev. Seventeen year-old Rina Shenrav was killed, and her father and brother injured. In the aftermath, settlement leaders called on the government to close the “superfluous” entrances to the Palestinian towns, entrances “that have no reason to remain.” I stopped the car.

“Good morning,” I said.

The older soldier, wearing glasses, answered me. “It’s closed here. You can’t pass.”

“How do I reach the main road?” I asked.

“Through a different entrance,” he said.

“Where?”

“I don’t know.”

I carefully made a U-turn on the narrow road.

“Ima, why are we turning around?” Forat asked.

“Just a minute, sweetheart,” I said. A Palestinian car, driven by a middle-aged man was driving down the road toward us. I waved to him through the open window.

“It’s closed,” I told him and asked if he knew an alternative route to the main road.

“Where are you going?” he asked.

“Tel Aviv,” I said, swallowing a rush of guilt, knowing he can’t drive to Tel Aviv. I’m not guilty, I reminded myself. I’m responsible. He was driving to Naalin, the last village before the checkpoint, and agreed to let me follow him. I returned to my conversation with Forat.

“You remember those people who stand at checkpoints?” I asked Forat.

“The ones who have trouble sharing?” she said.

“Yes. Well, they put up a checkpoint and are not letting us cross.”

“But Ima,” Forat said. “We’re Jews.”

I felt a pang in my heart.

“Yes, sweetheart, you’re right. Usually they let Jews pass. But here they think everyone is Palestinian, and so they closed the road to everyone, including Israelis.”

“Even to dolls?” Forat asked.

“What, sweetheart?”

“Even Israeli dolls?” She stuttered over the word dolls, re-learning how to speak Hebrew.

“I think so. Because the road is closed to everyone, and the Israeli dolls can’t cross by themselves.” There was a brief silence.

“Is it morning now for Diana?” Forat asked, referring to her best friend in Philadelphia, the daughter of an Israeli couple studying at the University of Pennsylvania and not planning on returning to Israel.

“It’s the middle of the night now for Diana-le,” I said. I thought of what Osama would say about our conversation. Among the many thoughts racing through my head was the realization that this was the first time I heard Forat refer to herself as Jewish.

“Forat, you remember that you and Adam are half Jewish and half Palestinian,” I said. “Because Ima is Jewish and Baba is Palestinian. And you are half from me, and half from Baba, and you can decide what you want to be.”

“Is Diana also half Palestinian and half Israeli?”

“No, both of Diana’s parents are Israeli and so she is all Israeli and also Jewish.”

“But do they let someone who is half-Jewish and half-Palestinian cross?” Forat asked.

“Usually yes. You and Adam and I can cross if there is an open checkpoint.”

“And Baba too?” she asked.

“Usually not.”

We continued driving the 40-minute detour through narrow, winding streets, the local roads of the villages on the ridge above the main road. The traffic was light on a quiet Friday morning, the day of rest in the West Bank.

“Ima,” Forat said. “Why didn’t you tell the soldiers?”

“Tell them what?”

“That they should share,” she answered.

“You ask a lot of good questions, sweetheart,” I said. “I would really like to tell them. But I don’t think they were ready to listen.”

“How do you know?” Forat answered. “You didn’t try.”

“How about I write down everything you’re asking and telling me this morning, and I’ll publish it so that the soldiers and also other people will read it? You’re such a smart girl, maybe they’ll listen to you.”

“OK,” Forat said. “Ima, I want another healthy chocolate ball.”

We reached the main street, and I recognized the entrance to the village of Naalin. I opened the window and waved in thanks to the driver who led us there, who now entered Naalin, the last village before the checkpoint. A young female guard from the private security company stood in the inspection lane, wearing a flattering black t-shirt and fitted black pants. A young man stood next to her, wearing a bullet-proof vest and carrying a huge M-16 rifle. She waved me on without even saying “good morning” to check my accent.

“Why did they let us cross now?” Forat asked.

“This is a checkpoint mostly for Jews,” I told her. “It’s almost always open.”

We reached the traffic circle in front of the settlement of Modiin Ilit. According to Waze, we would be ten minutes late for the ceremony at the cemetery. I called my cousin Amram and told him not to wait for us.

“Ima, is Uncle Shafiq still dead?” Forat asked.

This post was also published at haaretz.com on December 31, 2019:

https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/but-ima-we-re-jews-why-can-t-we-cross-the-checkpoint-1.8329358