In the four decades that passed between my U.S. grade school education and that of my daughter, Columbus Day lessons have changed, but not enough.

A capital city that’s also a nature reserve

I entered the apartment and took off my running shoes. “You won’t believe it,” I told my partner, Osama. “I saw two otters in the brook next to my running path.”

“What are otters?” asked seven-year old Forat. She and her brother, Adam, were sitting at the breakfast table.

“Like seals, but they live in rivers,” I said. “They jumped into the creek and played with each other close to the surface of the water.” The natural world in Raleigh, North Carolina, where we are living for Osama’s sabbatical year, is stunning. It’s as if the entire city is made of forest and creeks. On morning runs, I see deer, rabbits, owls, herons, turtles, and twice – coyotes.

“I like the system that Americans have here,” Osama said. “They think of everything, they plan conservation.”

Indigenous People’s Day

“If you want, we can go to the brook together,” I said and reminded the children: “There’s no school or preschool today.”

“Why?” Forat asked.

“Indigenous People’s Day,” I said. “Ms. Johnson didn’t talk to you about it in school?”

“No.”

“It used to be called Columbus Day,” I told her. “But three years ago, the State of North Carolina decided to recognize Indigenous People’s Day as a holiday.”

“What’s Columbus Day?” Osama asked. I told him that Americans celebrated the “discovery of America” by Christopher Columbus, an Italian sailor who got funding from a Spanish queen to sail to India, at the dawn of the era of modern European colonialism. His 1492 landing in North America marked the beginning of the conquest of the continent by Europeans, and the genocide they committed against the indigenous peoples who had lived in North America for thousands of years.

“When I was a child in an American school, in the 1980s, we would draw boats and hero-sailors scanning the sea with binoculars,” I told Osama. “By the time I reached high school, in a town with a diverse population, they understand that Columbus Day was problematic, but they didn’t know what to do with the holiday. They held a regular school day, but in the morning the school played a Latin American song over the loudspeakers, in Spanish, about three sons who left home for exploration. They were trying to extract from the holiday a celebration of the spirit of exploration.”

“Ms. Johnson taught us about the frontier,” Forat said. “And about Manifest Destiny and that the Americans went West.”

“Did you learn that there were people – native Americans – in the West, who were pushed out of places like North Carolina, and that the European Americans took their land?” I asked Forat.

“No.”

“So Golda Meir isn’t the one who created the idea that indigenous people don’t exist,” Osama said, referring to the famous 1969 statement by the then-Israeli prime minister, that the Palestinian people didn’t exist. In the United States, as in Israel-Palestine, many of those who came from Europe believed that God granted them the land, and that settling it fulfilled a national-religious commandment. The Manifest Destiny about which Forat learned is a nineteenth century doctrine holding that God destined North America for conquest by white Americans, whose race, religion, political regime and economic system were superior.

“Golda was perpetuating a centuries-old tradition,” I told Osama. “But it will take time until people here draw connections between Golda Meir and the American President Andrew Jackson, between sensitivity to Columbus Day and sensitivity to Israeli Independence Day.”

Israeli Independence Day

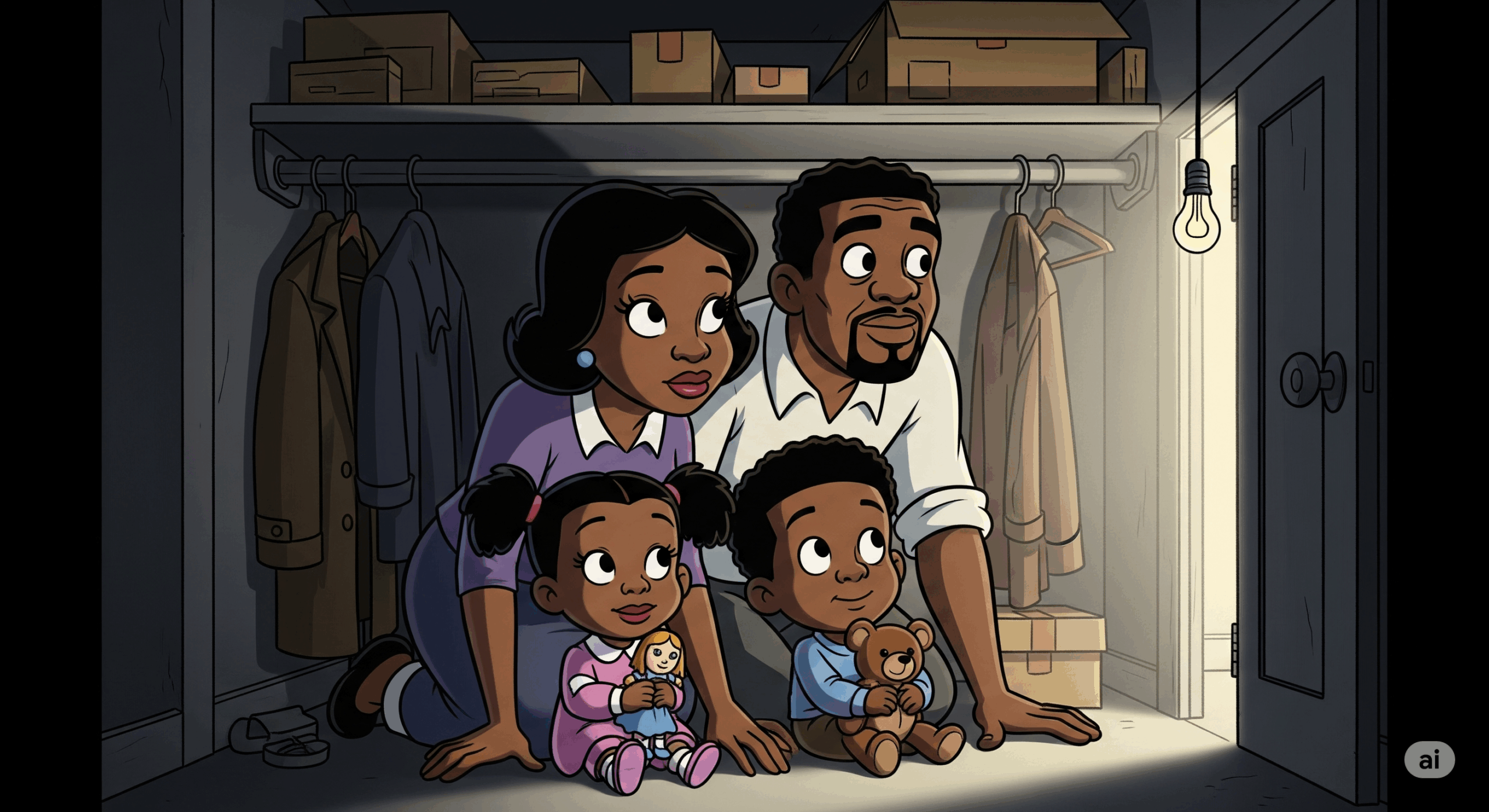

I was thinking of the troubling experience that Osama and I had with Adam’s preschool, an excellent school run by a local synagogue. The teachers there are professional, experienced, and loving, and they approach their work with a deep understanding of early childhood education. But last spring, Osama and I received a message asking us to dress Adam in blue and white, as part of the preschool’s celebration of Israeli Independence Day.

We were new to the American Jewish community, and in retrospect, I can say that we were naïve. We were surprised that that the preschool, founded on values of pluralism and tolerance, blurred the distinction between Judaism and Zionism. We didn’t know how to explain why we think it’s problematic to celebrate the establishment of the State of Israel without acknowledging the people who were pushed off its land, in order to create a Jewish majority, people such as Adam’s grandparents. Osama’s parents were forced to flee their homes in Majdal, now Ashqelon, when Zionist armed groups conquered the area in 1948. His parents were not allowed to return home. Adam has never met his grandmother, his uncles or his cousins, residents of the Jabalia refugee camp in the Gaza Strip, located just 90 kilometers from our home in the Ramallah area. That is because the same policy of Jewish demographic supremacy perpetuates, and it bars Palestinians from lands in the West Bank and Israel that the Israeli government designates for Jews. West Bank residents are not allowed to visit Gaza, and Gaza residents are not allowed to visit the West Bank.

On Israeli Independence Day, we kept Adam at home, while his preschool classmates drew Israeli flags and learned a very partial history lesson, similar to the lesson that I learned in school, nearly forty years ago, about the discovery of America. In those years, the teachers asked Native American children, too, to draw Columbus’s three ships, whose names are still engraved in my memory: the Niña, the Pinta and the Santa Maria.

Before European settlers conquered Raleigh, it sat between the territories of the Tuscarora, the Catawba, and the Siouan, native peoples who apparently used it as hunting grounds. These nations were destroyed in wars with settlers, died of diseases originating in Europe, were expelled from their land by militias and soldiers or fled the area, after they lost their source of food, as a result of the takeover of their lands. Today, Indians constitute just one percent of North Carolina’s inhabitants.

“Ima, do you agree with Indigenous People’s Day?” Forat asked me. I felt the burden of her trust: She’s asking me the question in order decide what is right and what is wrong.

“Yes, sweetheart,” I told her. “Ask Ms. Johnson tomorrow to tell you about it.”

This post was also published on Haaretz.com on October 18, 2021:

https://www.haaretz.com/.premium-a-family-from-ramallah-confronts-america-s-columbus-day-1.10304362

Your essays always touch my heart and trouble my conscience as a white male American, and now especially this one, mindful that I also grew up drawing Columbus’ ships, and doing skits about him and Queen Isabella in elementary school, and memorizing the names of his ships.

Thanks for sharing, Tom. Yes, it’s amazing how potent those childhood lessons are.

שרי יקרה,

הלב נחמץ והאגרוף נקפצת. גם על הפן האישי עליו את כותבת וגם על הפן הכלל אנושי. ההיסטוריה האנושית מלאת עוולות, חטאים ודם שנשפך לריק. אבל את ההיסטוריה כותבים כידוע המנצחים ונחוצים המון עקשנות, נחישות ועבודה סיזיפית כדי שקולם של שרידי העמים שנכחדו או שנלחמים על זהותם ועל הכרה בהם, ישמע ושיקבלו את מקומם הראוי בסיפור הכלל אנושי.

גם בשבדיה בה אני גר יש פרקים אפלים של עוולות וחטאים היסטוריים.

מחכה לפוסט הבא

בידידות

יהודה שרל

תודה, יהודה!

The similarity of the ethnic cleaning of Palestine and the ethnic cleansing of all land west of the Atlantic is stunning. I figure Americans would run into conflicts of conscience if they tried to stop Israel from completing the vision of Ben Gurion, i.e. taking over all of Palestine and possibly quite a bit more. How could they criticize Israel’s colonial enterprise while their own history had the very same beginning. What I find very disturbing is that the UN, too, has not found the courage to call the 1948 partition vote a screaming miscarriage of justice and to apologize for it AND tell the voting powers that were in 1948 that as long there is no accounting of that act of injustice the Palestinian people have every right to resist the completion of the Zionist project. Many people say the Israeli-Palestinian conflict bears many layers of complexity… it does not.

Thanks, Gunther. Reminds me of something a football (soccer) friend of mine used to say before pick-up games: “Football is a simple game that only idiots complicate” 🙂

מגיב בלייק, בהזדמנות זה שווה פוסט ארוך- לגבי עמים ילידים, וכן לנושא שני מדינות לשני עמים. לא מאמין במדינה דו לאומית מסיבות רבות.

תודה, עמירם!

מה ההתרגשות? נדמה לי שאת כל ההיסטורי של המין האנושי כתבו המנצחים. והשמות, ציורים, ופסלים, נתנו בהתאם. לא המצאה של הציונים. אוהב את הטורים האנושיים שלך ושל משפחתך, אך כשמגיע לפוליטיקה, נראה לי קצת תמים.

מכיוון שלמדתי/נו באוניברסיטת קולומביה, לא הייתי רוצה שיישנו את שמה כעת.

המשיכי בהצלחה

תודה, משה, על ההערות ועל התעניינותך בבלוג.

The similarities between the founding of the United States and the founding of Israel are astounding. Both countries were built with the ethnic cleansing of the people already on the land while the ethnic cleansers were and still are exalted.

Thank you, Jan.

Again: much food for thought. Thank you!

Thanks!

The parallels are astounding and shameful. I too grew up with Columbus Day and only recently have references been made to Indigenous People’s Day. Waiting for Israel to make such acknowledgments as well.