Supermarket workers push customers out as 5 P.M. approaches. ‘Police,’ they whisper apologetically to those who seem surprised at their uncharacteristic strictness on lockdown rules.

Zoom Kindergarten

The animated boy in the video plucked the chick’s feathers. In the corner of the computer screen, Forat’s French kindergarten teacher, Miss Chantal, sang along with the narrator: “La petite poule rousse!” Adam, her brother, dragged a kitchen chair to the desk and tried to get closer to the computer. Forat pushed him away. Adam screamed. I muted our microphone. Adam hit Forat. I picked him up.

“Ima, why is the boy plucking the feathers?” Forat asked me.

“Ask Miss Chantal,” I told her.

“No, you ask.”

I unmuted our microphone and asked.

“The boy wants to eat the chicken,” Miss Chantal started to explain in French, but she stopped when Forat’s face disappeared from the screen. “Can Forat hear me?” she asked me in English.

“Yes,” I said. “But she’s hiding under the table.”

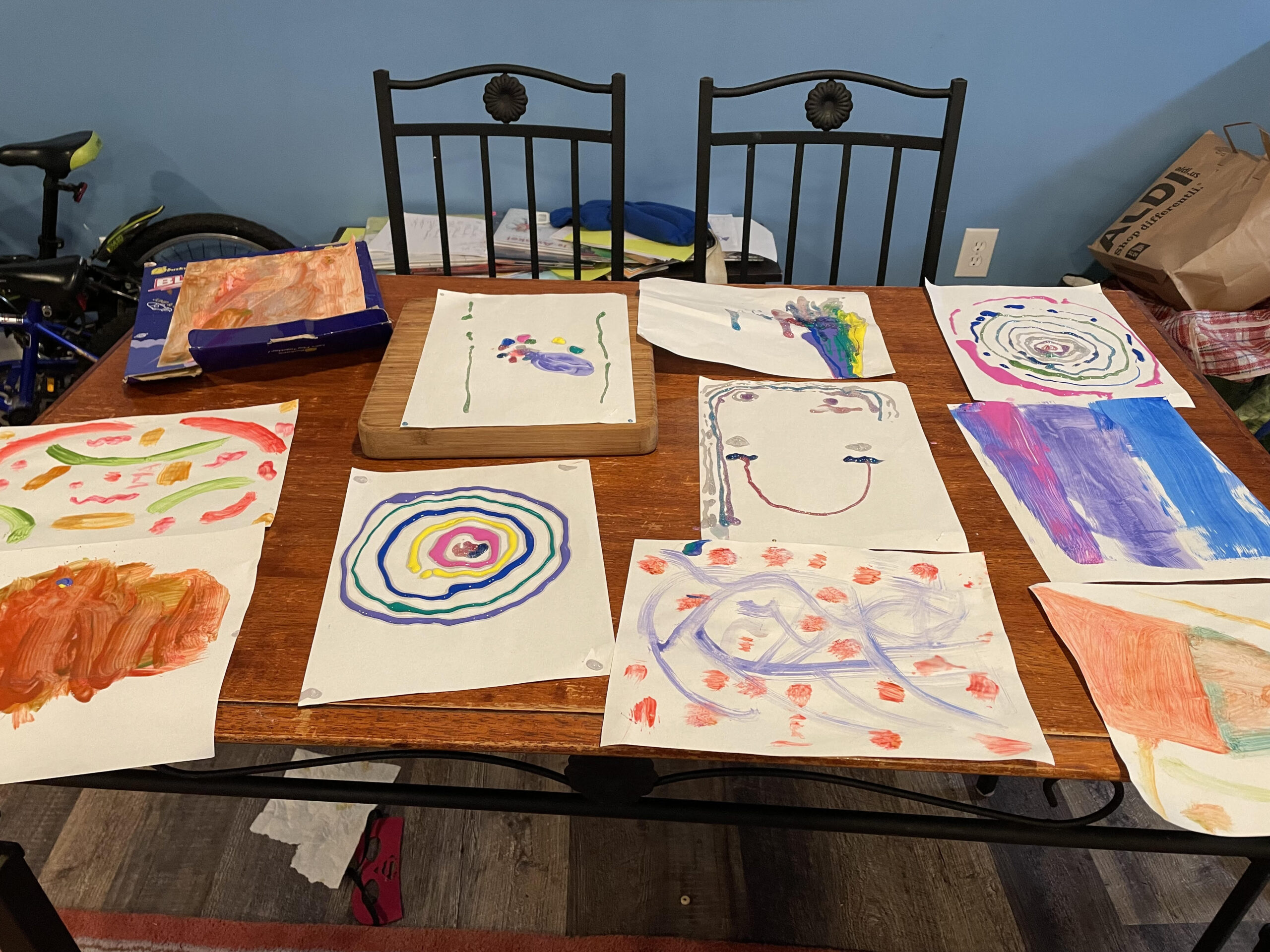

Miss Chantal has amazing reserves of energy. Her remote learning program terrifies me. Every week, we get dozens of worksheets for Forat to draw, cut and trace, in French, Arabic and English. Except that we don’t have access to a printer, my accent in French horrifies even Forat, and anyway she refuses to look at the materials. If I insist, Forat deliberately gives wrong answers to check my reaction.

I wrote to Sawsan, after I noticed that her son Salah was absent from the Zoom lessons.

“Salah refuses to have anything to do with the kindergarten,” she wrote back. “I gave up.”

I felt relieved. I can barely get Forat to brush her teeth and stop hitting Adam. My attempts to have us create a daily schedule failed miserably. She would only agree to write tasks such as “Make brownies” and “Draw Hello Kitty.” I feel like we spend every day just trying to survive, while simultaneously feeling grateful for our good luck: We are healthy, we have a house and food, and the children enjoy spending their days making up games, usually the kind that requires them to empty the contents of the closets and drawers up to a height of one meter from the floor.

Surprising Enforcement of Lockdown Rules

In Palestine, there have thus far been 291 confirmed cases of the novel corona virus, and two people have died. We are at the end of our sixth week with no daycare or school. We are allowed to leave the house between 10 am and 5 pm to buy food or medicine. This week, they announced that a limited number of additional stores would be allowed to open during those hours, only on Fridays. Police cars line the central streets of Ramallah/Al Bireh, and police officers check licenses and interrogate the drivers. Supermarket workers push customers out of the stores as 5 pm approaches – “police”, they whisper apologetically to those who seem surprised at their uncharacteristic strictness.

For good or for bad, in the residential parts of town, the police don’t interfere with solitary sports activity. I still run every morning. One morning I decided to run to the center of town. Here and there workers unloaded produce for grocery stores. The central market was closed. When I stopped to photograph a flock of pigeons resting on what was once a busy street, a policeman wearing a face mask motioned for me to approach.

“You’re not allowed here,” he said.

“I’m running by myself,” I answered.

“Go home,” he said.

Please don’t come close

A friend whose family lives near Bethlehem told me her brother held a dinner for eighteen members of their extended family. “I tried to explain to him,” she told me over the telephone, with resignation.

When I went outside to throw out the garbage, our neighbor from across the street invited me to visit with the children.

“I can’t now,” I told her, making a wide arc on my way to the dumpster to keep my distance from her. I was afraid of offending her, and I was afraid of getting close to her. “I’m not really afraid for my family, but I don’t want to give the virus to someone else,” I said apologetically.

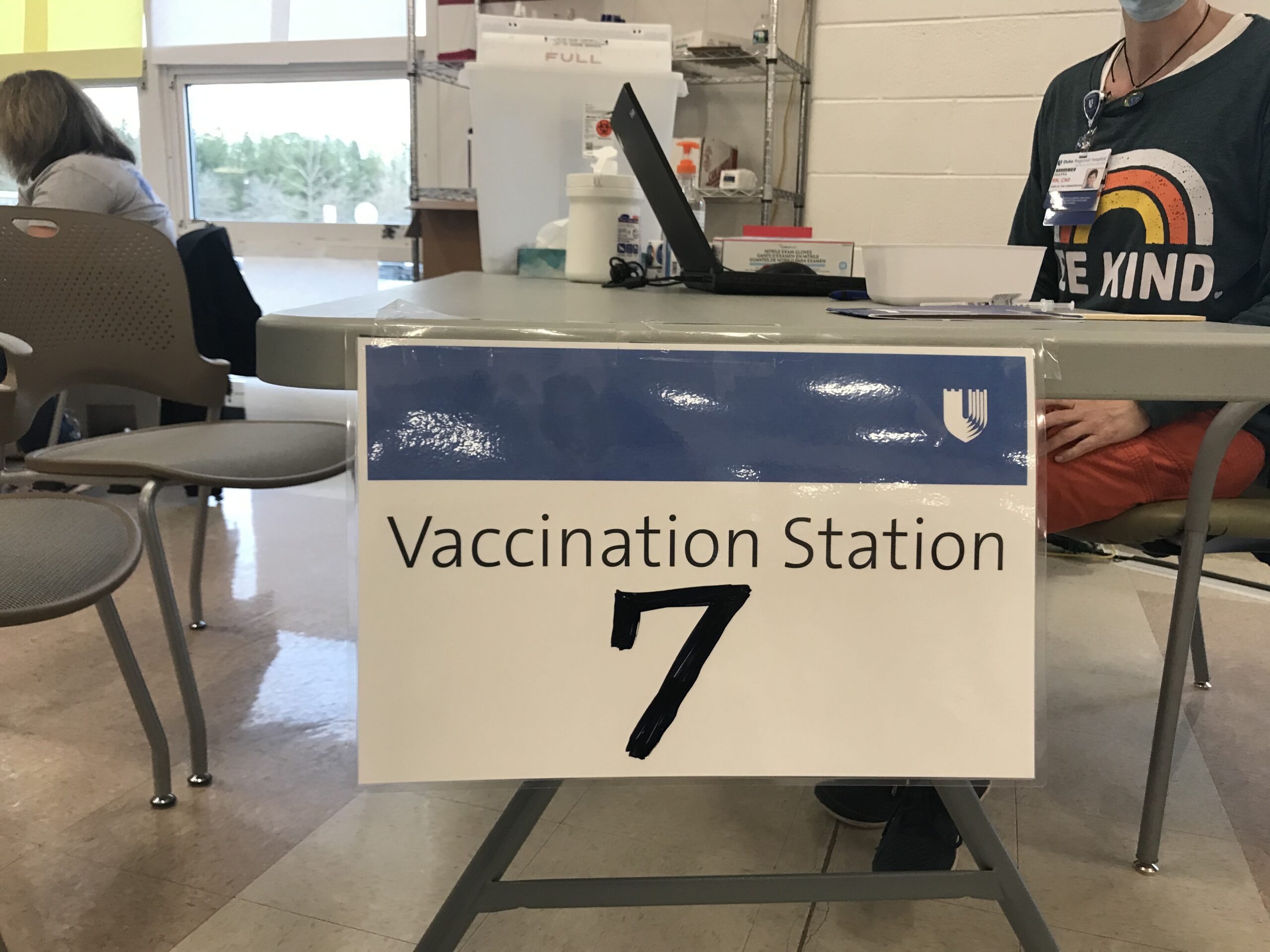

“This is not Italy,” she said. “The problem there was that people don’t get vaccinated.”

“There is no vaccine for the corona virus.”

“Yes, but the vaccines we get as children strengthen our immune system.”

“I would love to come when this is over,” I told her, without knowing what it would mean to be “over”.

I threw away the garbage and looked around. Children played football in the street. Cars zoomed by. People – who clearly were not family-members – gathered in groups of two or three: high school kids leaned in to read something on one of their telephones, young men walked together, their hands on each other’s shoulders, and teenage girls spoke to each other in conspiratorial whispers. I felt a wave of sadness, of fear.

There is a plan to contain the corona virus in Palestine, and the authorities are following it with surprising strictness. But if the virus spreads – it’s not clear how they will deal with the consequences. In the Gaza Strip, for example, there are 120 intensive care beds for two million people. Because of equipment shortages, only about 2,000 corona virus tests have been conducted for Gaza residents. In refugee camps throughout Palestine, distancing or quarantine is impossible. Maybe that sense of vulnerability explains the masks that people have started wearing in the streets of Ramallah, the transparent plastic shields erected between the cashiers and customers at the larger supermarkets, and the police activity. But we are nearing the month of Ramadan, when Muslims fast by day and then invite people to elaborate break-fast dinners. Tens of thousands of Palestinians have begun returning to the West Bank from their jobs in Israel, some of whom were infected there. And this week, 4,000 Palestinians are supposed to return to Gaza from travel abroad via the Rafah Crossing with Egypt. One mistake would be irreversible.

I opened the door to our apartment. Forat was wearing a light blue ball gown and red lip gloss on her cheeks, eyelids and also her lips. “Guess which princess I am!” she said. Adam came running toward me. I lifted my un-washed hands above their heads.

If the children or I got really sick, we would drive to Hadassah Hospital in Jerusalem and get excellent care. That is not the case for those we would infect, including my partner, Osama.

“Wait, sweethearts,” I said to them. “I need to wash my hands.”

This post was also published on Haaretz.com on April 6, 2020: