How can we teach our children to resist what is wrong in society – while still protecting them? Boys in dresses and girls at demonstrations.

Two and a half-year old Adam likes to wear dresses. Also skirts and pink shirts. They belong to Forat, his six year-old sister, whom he emulates in everything else, too. He watched her twirl around in circles to make her skirt dance, hold wedding ceremonies with Red Teddy Bear as the groom and reign over her queendom in a ball gown and crown she made from colored paper – and decided that he wanted to get in on the fun.

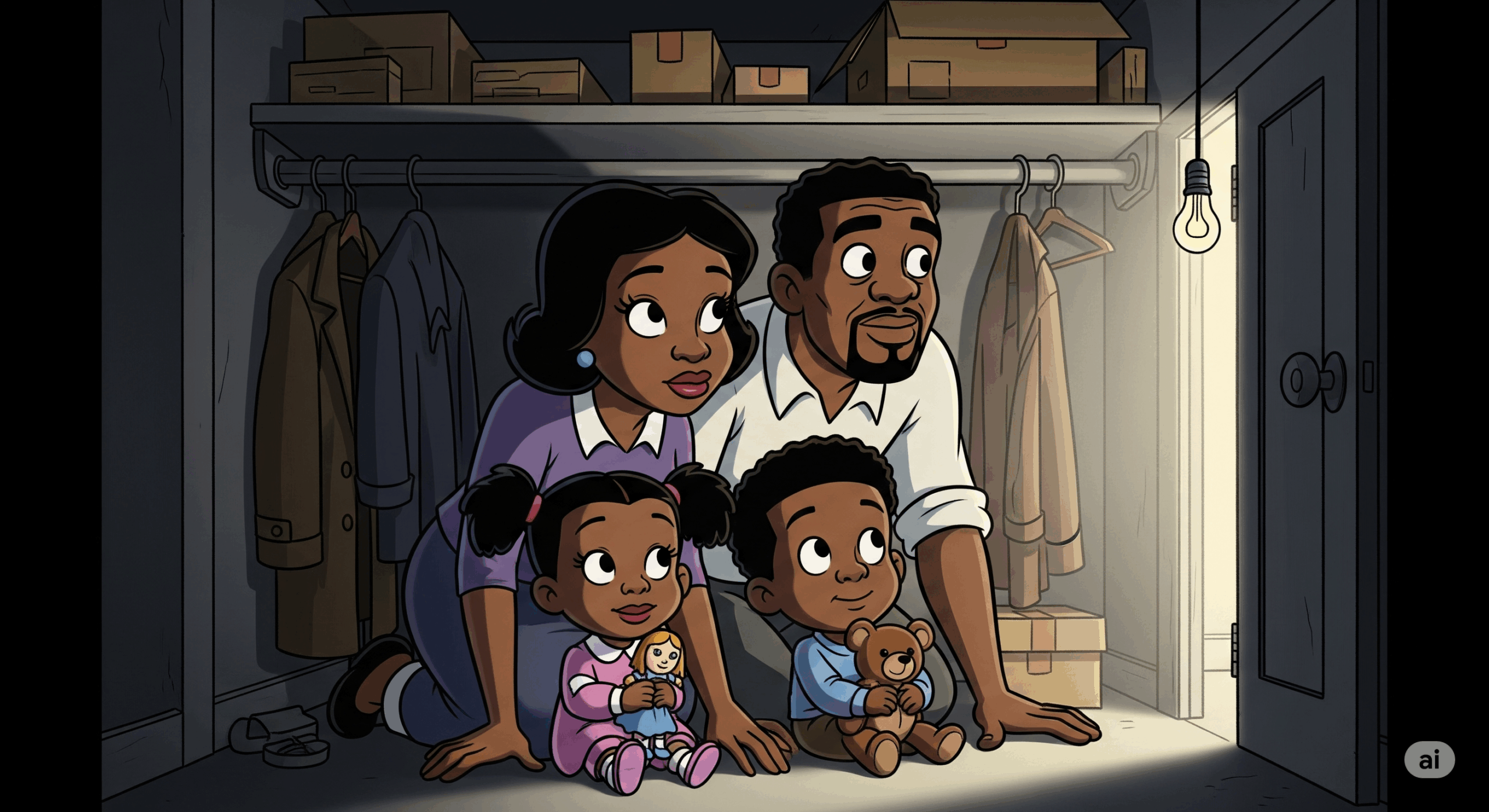

“White dress!” he demanded when he came home from daycare, and he raced to the closet to select one of Forat’s dresses. The look of joy on his face as he twirled around was adorable. But then came the dilemma.

“Sweetheart, let’s wear pants to daycare,” I suggested the following morning.

“Biddush!” he answered in his slightly jumbled Arabic. “Biddi Fustani!” “I want my dress,” which in this case was purple with a wide, flowing skirt and a shiny picture of popcorn. It’s hard to blame him. His clothes are in solid colors of red, blue or black, at most with a picture of some dinosaur or tractor, and totally devoid of sequins or fairies.

“The dress is too big for you,” I said, but that wasn’t really the point. I mean, we could have bought a dress in his size. I asked myself: Why not do so?

“Let him go to daycare in the dress,” I told Osama. “His daycare claims to be progressive.”

“I’ll bring a pair of shorts for changing,” Osama said.

“Why?”

“In case he wants.” Meaning, in case the daycare teachers want.

Adam’s arrival at daycare was uneventful, and the teachers refrained from commenting on his clothing. We continued to let him wear Forat’s dresses, and he was thrilled. But children and adults – Palestinians, Israelis and Americans, on the street, in the homes of friends, in video calls with family members – kept raising questions and objections, and I was worried that Adam would sense the negative feedback.

“Ima, Karam said that boys are not allowed to wear dresses,” Forat reported to me at the playground.

“And what do you think?” I asked, hoping to incite her to a healthy rebellion against restrictive social norms.

“I want Adam to stop taking my Minnie Mouse dress,” Forat answered. “He spilled ketchup on it.”

“Forat, yesterday you told me that Miss Nibal said boys can choose pink paper if they like, right? Because everyone should be able to pick the colors they like.”

“Miss Nibal also said that we are naughty because we didn’t listen to her words, and that she will punish us,” Forat answered.

So much for relying on Miss Nibal to challenge conservative notions of educating children. I made a quick U-turn: “You know that Ima and Baba don’t always agree with Miss Nibal. We think that all the children are good, and if they make mistakes, the teachers should help them correct them.”

Forat didn’t miss a beat: “If you don’t agree, why do you send me to that kindergarten?”

Sometimes I feel like most of my conversations with Forat – and I guess it will be the same with Adam – are composed of me saying, “This is how the world is, and Ima and Baba don’t agree.” Why I don’t wear shorts outside the house in Ramallah, why her father can’t come with us to my cousin’s wedding in Tel Aviv, what is a gun and what people do with it. I want to give my children the freedom to be who they want to be. I want them to challenge the flawed world in which they live. And I also want to protect them. How do other parents strike a balance?

On Saturday evening, I took the children to a demonstration in Tel Aviv. Forat and Adam loved the noise, music and socially-distanced crowd. Adam, wearing a flattering floral dress, stood on the edge of the fountain in Rabin Square where huge goldfish swam, pointing and screaming: “Samake! Samake!” Fish.

The organizers distributed fluorescent stick lights for a minute of silence in memory of Eyad Halaq, the Palestinian man with autism who was shot to death by Israeli border guards in Jerusalem. Forat mingled among the demonstrators, who stood on X’s taped to the ground two meters apart, and collected the stick lights they dropped, weaving them into a rainbow.

“Who is Eyad Halaq?” she asked.

“Someone who wasn’t treated nicely,” I answered.

When Forat asked what is “occupation,” I told her that it’s when people don’t want to share. We tell Forat that her father, who is Palestinian, can’t cross checkpoints because the people standing there have trouble sharing, and that Ima and Baba don’t agree. I added that the demonstrators also disagree with the occupation and are calling for it to end.

Forat listened to the chanting and speeches, in Hebrew and Arabic, her eyes wide and alert. At 9 pm I tried to persuade her to get into the stroller, next to her sleepy brother.

“Ima, is the demonstration over?” she asked.

“Yes, sweetheart. Everyone is going home, and so are we.”

“So Baba can come now?” she asked. “To Tel Aviv with us?”

“Not yet, sweetheart. It will take time until the people at the checkpoints agree to share.”

“So then why is everyone going home?” she asked. I felt a surge of pride. Maybe she will insist in the places where we adults have given up too easily.

“Because Baba is waiting for us at home,” I said, and I gave her my hand to help her climb into the stroller.

This post was also published on haaretz.com on July 1, 2020: https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/my-son-insists-on-wearing-dresses-in-ramallah-1.8962279

אום פורת,

מרגש ועצוב לי לקרוא על הקשיים שאת ואוסמה צריכים להתמודד איתם בגלל המצב הלא נורמלי שקיים בישראל. מקווה שפורת ואדם יוכלו למצוא את מקומם במציאות הלא פשוטה הזאת.

התאהבתי לפני שנים בבחורה הולנדית לא יהודית, (אלוהים ישמור) בטיול בחו”ל . אחרי 4 שנים שגרנו בארץ בחרנו לנסות לחיות בהולנד.

היום, עשרים שנה קדימה אנחנו חיים חיים יותר נורמלים, עם שלושה בנים שלא צריכים להתגייס ולקחת חלק בדיכוי של בני אדם אחרים.

כמובן שאני מתגעגע לדברים מסוימים בארץ אבל המחיר של הגזענות כנגד האדם הלא יהודי בישראל גרם לי לבחור להגר מרצון. לאור השינוים בארץ בשנים האחרונות נראה לי שזה גם היה הצעד היותר מנכון…

מאחל לך ולכל משפחתך חיים טובים ומאושרים באשר תבחרו לחיות.

אמשיך לעקוב מרחוק…

2025 im curious. Update. Is Adam still interested in his sister’s clothing? And I love how u and your husband responded when he chose to wear them.

Thanks! No. The gender socialization here is very strong, as it is in many places. Kids learn what they’re “supposed to” like.