Most deep natural pools in the West Bank are near settlements, and settlers have taken them over, by arriving there with guns or Israeli soldiers.

Our relationship exposes my partner, Osama, to the seam areas of the West Bank, where Israeli settlers encroach on Palestinian towns. Before we got together, most of Osama’s encounters with Israelis were with soldiers at checkpoints and detention centers. He usually stayed in the bubble of the Ramallah area, which Israeli settlers and even soldiers rarely enter during the day. But I like going on family hikes in the West Bank, and the nicest places are also popular with Israeli settlers.

On the last day of the second coronavirus lockdown in Israel, I persuaded Osama to go for a hike in the Auja wadi or stream, in the Jordan Valley, near the Palestinian village of Auja. Most of the other deep natural pools in the West Bank are near settlements, and settlers have taken them over, meaning they arrived at the pools with guns or under the guard of Israeli soldiers, thus deterring Palestinians from bathing there.

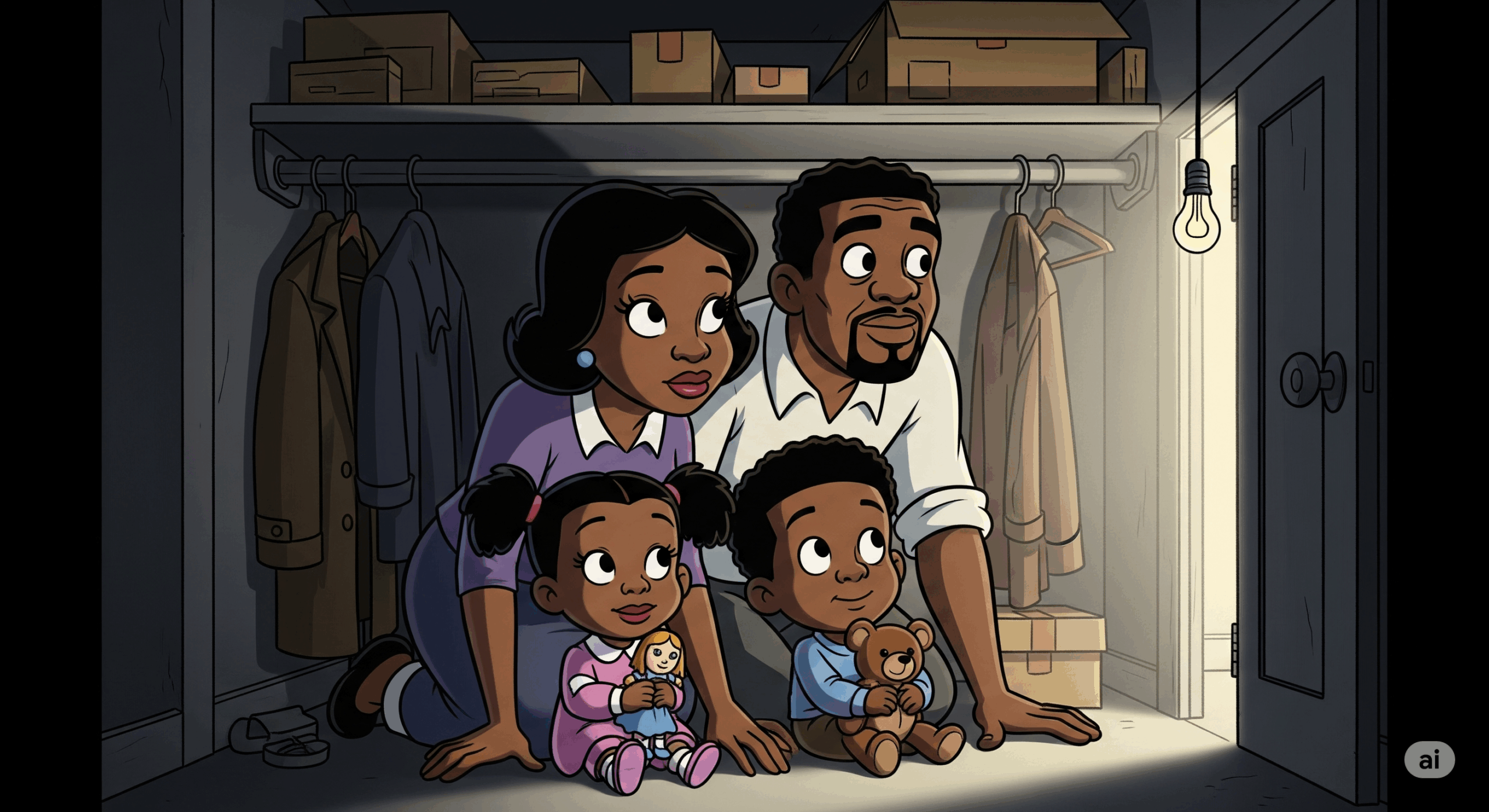

“Are you sure it’s safe?” Osama asked, after I started the car and pulled out of our street, with six year-old Forat and three year-old Adam in the backseat.

“We’re in my car, an Israeli car, so they won’t stop us,” I said, because police officers tend to stop Palestinian cars on the roads used by both settlers and Palestinians. “And today is Saturday – most settlers don’t drive on the Sabbath.”

“When we went to Wadi Qelt, also on a Saturday, we saw two groups of armed settlers,” Osama reminded me.

“It’ll be OK,” I said. “Israel is still under lockdown, and the restrictions are supposed to apply to settlers in the West Bank, too.”

“But if Israelis are not allowed to leave their homes, what does that mean for you?”

“That I’m not supposed to travel further than a kilometer from my registered address in Holon,” I said.

“And if they stop us?”

“You’ll do the talking, and I’ll be your obedient and silent wife,” I said. And then I realized – we would be more persuasive if the obedient wife didn’t sit in the driver’s seat. “Actually, on second thought – we should take your car,” I said. I made a U-turn. “Sorry sweethearts, we have to go home and take Baba’s car,” I told Forat and Adam.

“Why, Ima?” Forat asked.

Osama and I looked at each other. I started to laugh. “Do you want to explain it to her?” I asked him.

We drove toward Jerusalem, along the Separation Wall. As we approached the vicinity of the Qalandia checkpoint – where traffic from three urban centers is funneled into a single, crowded traffic lane – we slowed. Osama fought with drivers who tried to cut him off and even drive in the direction of oncoming traffic. We continued driving along the wall, making a wide detour around the city of Jerusalem, which was on the other side of the wall, to reach the road to the Jordan Valley. We slowed at a mobile checkpoint and saw two police officers questioning a young Palestinian driver on the side of the road. Osama’s body tensed.

“Why did you have to insist we hike in this area?” he asked.

We continued on the Jordan Valley road. The Palestinian villages were either not marked at all or marked with red signs warning Israelis not to enter them. At the point where villages met the main road, there were yellow gates that allowed the Israeli military to close off access. Hebrew-language road signs prominently marked the names of settlements and nature sites. The signs for cities such as Beit Shean – “Bisan” in Arabic – were in Arabic, too, but listed the Hebrew names in transliteration, written in Arabic letters.

We reached the parking lot that leads to the Auja spring. I heard Hebrew. A group of hikers got out of their car, including two women in skimpy sleeveless tops not often worn in Palestinian villages. The Palestinian hikers and the vendor selling hot corn in cups fell into silence until the group left the parking lot for the trail.

“At least they’re not carrying guns,” I said to Osama, and I tickled his armpit to make him laugh. He pushed away my fingers and did not laugh.

“They’re not openly carrying guns,” he corrected me.

I ran with the children up the trail. Osama walked behind us, disappointed by the piles of garbage that other hikers had thrown along the banks of the stream.

“Palestine is beautiful,” he muttered under his breath.

The water was cold and clear, despite the food wrappers floating in it. I encouraged Osama to relax on the banks and took the children to look for the spring at the stream’s source. I showed Forat the trail markings of the Israeli Society for the Preservation of Nature: a red line inside a white border, painted on the rocks. Like most of the Jordan Valley, Auja Stream is in Area C, under full Israeli administration. The Israeli settlement of Yitav is nearby, as is the Bedouin high school that is under threat of demolition, as part of an Israeli policy to prevent Palestinian construction in the Jordan Valley and ultimately – to annex it.

We passed a 50-something Palestinian hiker who had stopped to rest on a rock. He heard me speaking to the children in Hebrew. “How are you?” he asked me in Hebrew, and I said, “OK”, also in Hebrew.

But when he addressed Adam in Hebrew I responded in Arabic: “The boy speaks Arabic, too,” I said, “He’s half Palestinian.” I’m not sure what he understood from that or what I was trying to tell him. It’s rare for the children and me to be in an area with both Palestinians and Israelis. It’s rare, because there aren’t many places where the groups have contact with each other. Those places are usually disputed areas, where your identity determines which side you take.

We reached the source of the stream that fed into a large, clean, and beautiful pool. We saw two groups of hikers, a Palestinian group of three men and an Israeli group of three men and one woman. All of them turned to look at us, trying to classify the children and me. I wore a t-shirt, crop pants and no head covering. The children ran to the water’s edge.

“Ima!” Forat called in Hebrew. “Take me to the waterfall!” The two groups averted their gaze from us, as if they had gotten an answer to their question. But then Osama arrived, and Forat ran up to him.

“Baba!” she yelled in Arabic. “There are fish here!” All seven hikers turned their heads and stared at us again.

“Let’s go for a swim and confuse them,” I said to Osama. “It’s beautiful and clean here.”

“Yes, but there’s no shade,” he said.

“Actually, there’s shade over there,” I said. “But guess who took it over …” I pointed to the group of Israelis. They had tied a hammock to the branches of the only tree around. They sat in a circle in the small pool at the source of the stream, like in a natural Jacuzzi, and sipped from beer bottles. Someone – not them – had painted blue and white Israeli flags on the rocks next to them, and someone else had partially covered the flags in black spray paint.

I searched Osama’s face and was relieved when he smiled.

“Yes, your people indeed know how to create facts on the ground,” he said, and splashed water on me.

This post was also published on haaretz.com on November 12, 2020:

https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/searching-for-a-safe-place-in-the-west-bank-for-a-family-hike-1.9303475?fbclid=IwAR2eCguC0ZRt0nRUU6raIp8IQqHxgLcfsO-6_ma57ytsro-RrMfC44bX3kw

Thank you so much for sharing your experiences. My heart goes out to you and your family. I am a Jewish Israeli woman, married to an African American Sikh, living in the US. You can imagine the looks we get – a black man wearing a turban and a white woman who speaks with an accent. I can so relate to your partner’s unease when facing settlers, the same anxiety I feel when my husband is out, driving while black. And still I am encouraged by your determination to live as normal life as is possible in our world, and hope that some time, maybe for your children, things will change.