Children are aware of stratification by gender and ethnicity. They notice who works in preschools, who their parents’ bosses are, and who cleans public toilets.

Rereading a book from my childhood

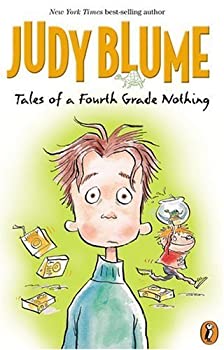

Forat lay on her bed and lifted her eyes from the book in her hands. “Ima, why doesn’t the father know where the food in the kitchen is kept?” she asked. She was reading a book called “Tales of a Fourth Grade Nothing,” about the relationship between a nine-year old boy and his three-year old brother. I joined her in reading the chapter describing how the mother goes away for the weekend and leaves the boys with their father, who has no idea how to take care of them or the apartment.

“They want to show that the father doesn’t know how to take care of his children,” I told her. “As if he only goes to work.”

“But why?” Forat asked.

“Some people think that mothers should stay home with their children, and that men don’t know how to be good parents,” I told her.

“But you don’t agree, right?”

“Right.” I said, and then I added: “You know that there are people who will tell you that because you’re a girl, you’re not as good as boys or that there are things you can’t do. And they are wrong.”

I was thrilled when I found that beloved book, familiar from my childhood, in a little street library in Raleigh, North Carolina, where we have lived for the last year. After the conversation with Forat, I re-read it. The author, Judy Blume, is considered to have been a pioneer: In the 1970’s and 1980’s, she wrote frankly about children and teenagers dealing with adolescence, menstruation, their parents’ divorce and sex. Now I discovered things in her writing that I hadn’t remembered, maybe because, at the time they were written, they were the norm for children’s literature in the United States: The characters were upper middle class and white. The mother cared for the children while the father worked in an office. The father’s work colleagues were men, except for a secretary, who was described as obsessed with her hair and makeup. In the apartment building where the family lived, there was an elevator operator who called the mother by her family name, ”Mrs. Hatcher,” while she called him by his first name, “Henry.” The mother was described as emotional, and the father was portrayed as disconnected from his family.

Protecting our children

“We’re not like you, we don’t want to expose our children to complicated social problems,” Diana told me. She’s Israeli-American, white and of Ashkenazi descent, living in the United States. “At this stage of childhood, they’re in a kind of paradise, and we’ll let them stay there for as long as possible.”

“They’re not in paradise, they’re living in an unequal world,” I said. “Your children observe, consciously or unconsciously, that most of the other kids in their private school are white, that the people who work as cleaners are primarily brown and Black women, and that most of the professors at the university where their father teaches are white. The question is what meaning they give to these facts.”

“I understand that it’s like that for your children, because of your circumstances,” Diana said. “But my children have not been exposed to things like that yet, and I want to protect them for as long as possible.”

Children learn by observing the world around them

We are a mixed family, Israeli-Palestinian, and we usually live in the Ramallah area. Diana is right that we couldn’t have avoided explaining to our kids what a checkpoint is, why their father can’t join us for an outing to the sea and why their father and mother are not allowed to drive the same car. Forat asks questions, and we answer them, because her life is directly impacted by the inequality and oppression in Israel-Palestine. We have to scramble to get permits for her father, take precautions on roads frequented by soldiers or settlers and buy two cars. But since we moved to the United States, where we enjoy the privilege of being a “white” family, I have come to believe that it’s even more important to address the questions our children don’t ask, about the stratification that may seem less jarring to them, because in the United States, unlike in Israel-Palestine, they belong to the privileged social class.

Three years ago, we lived for a year in the United States and enrolled our children in a preschool in a racially diverse city. The director there relayed a story about how the teachers address stereotypes that even small children bring: A three-year old white boy saw a Black man approach the preschool and mistakenly thought he was a janitor. In reality, the man had come to the preschool to pick up his son. The boy’s mistake was disturbing but also understandable. Children absorb what they see and hear and use it to put together a picture of our world, flawed as it is.

A week ago, I took Forat to the eye doctor. The woman who sat outside the clinic and checked our temperature was Black. The technician who checked Forat’s vision was a white woman, and the doctor was a white man. That stratification of roles according to gender and ethnic identity repeats itself in countless interactions. Small children notice who works in preschools, who drives trucks, who are their parents’ bosses and who cleans the public toilets.

Irrespective of her unusual circumstances in Israel-Palestine, Forat does not live in paradise. I don’t think she’s unique in that. Few children are blind to the oppression and inequality that characterize nearly every human society. The question is whether they think that is how things should be, or whether we can help them develop a critical approach to that stratification and the motivation to try to change it.

This post was also published on haaretz.com on December 29, 2021:

https://www.haaretz.com/us-news/.premium-when-a-beloved-book-from-your-childhood-brings-up-troubling-questions-1.10499351

Shalom/Salaam Dear: Bless your heart, Sister! I admire and respect you and all parents who have this challenge. To your question, “when,” I would suggest when they ask, or when they witness an injustice or an oppression., not to let it go by, but to “process” it, otherwise, they will process it for themselves, and developmentally, they will make age-nonappropriate sense of it, which can be confusing and painful. But also all along I think parents may want to have children learn by parents reading them great books, encouraging them to make friends with all kinds of kids, and for parents to be an example by having diverse friends, and by having friends over to the home from everywhere. From my experience in 1950s America, it was right after WWII, another time, but as Jewish people and especially Jewish children, many of us were terribly afraid of non Jewish people. We became an isolated community, socializing mostly with other Jewish families and our own families. Now that I’m a Muslim in America, I meet all kinds of people from everywhere around the globe, and I love it. I have to tell you a story from our mosque Sunday school where I’m a teacher. One Pakistani young girl was telling me about injustice she was experiencing at school from kids who were bullying her due to her dark skin, calling her “Paki,” etc. I listened and offered support and encouragement, and at the end gave her a big hug. She looked at me through tearful eyes, and said: “White people sure do stink, don’t they?” Laughing, I said, “Yes, they sure do sometimes.” What she didn’t realize because I’m a Muslim who wears a hijab, is that I’m a White person, lol.

Umm forat I love your writing I love your message you’re brilliant you’re an amazing woman I wish you well at all your endeavors keep writing never stop

Dear Sari, you are touching this topic with a very sensitive pen and I agree with every word of what Safiyyah says in her comment

Born in Israel, living in Sweden and (was) married to a Swede we brought up our three children to be “political animals”. We cannot run away from

this complex and we have to prepare them to face the realities of life

with all the challenges it means, to teach them to embrace every human being as such , as equal! Period

I am a pediatrician, now retired. In training, at an Ivy League institution, we were taught all sorts of things about children, developmental stages, how to discipline and praise, how children process divorce, etc. etc. I do not remember having been exposed – so straight forward, observing, artfully and loving – to the realities in our stratified world as your children do in your and your partner’s complex world.

אום פוראת, אני נהנית מאוד לקרוא אותך. חכם, רגיש ומעניין. ראשית האם עדיף לך שאזמין את הספר (אותו אני רוצה לקרוא) דרכך או דרך הוצאות ספרים בארץ? ולגבי חינוך ילדים – אני מאוד רוצה לדבר עם נכדי על נושאים אלו, הבעיה היא שהם לא שןאלים. הם כל כך רגילים למציאות של אי שוויון שהוא אפילו לא מעלה בהם שאלות. זה נראה להם טבעי שאריתראי מנקה את הרחוב, ושאחד בונה בניין ואף אחמד לא גר לידו אלא הולך עם שקית הניילון שלו הביתה, מעבר להררי החושך מבחינתו. מבחינה מגדרית דווקא יש שוויון בבתיהם , אבל על המציאות בישראל הכובשת, הגזענית , המפלה לא מדברים. זה מציק לי כי אני בן אדם מאוד פוליטי.

Children learn by observing, from they are babies – seeing smiling faces/soft voices – sour faces/hard voices – and putting together what they see, hear and experience to their first understanding of life, family and society. I think you choose the right way when you tell your children how “things are” because you will do so with love and wisdom.

Enslavement is as present as hatred & privilege segregation. Fortunately, as long as there is free will, the will to succeed in goodness will triumph. Once free will is taken, either find a hiding place or face death with courage. We have meaningful work to do with our freedom to choose our own attitudes & hopefully actions. Family & by extension, nations, are built on iron clad free will. Let us celebrate our good fortune with diligence & trust between those of like hearts. With a strong core of those who hunger & enforce personal freedoms, we will create a force for dominance. Even children do not need to have it described. They will recogize what their conscience applauds.

Sandy Rinaldi, Arkansas, US Army veteran 1971 to 1974

29 DEC 21 When OK to teach children on oppression 28 dec