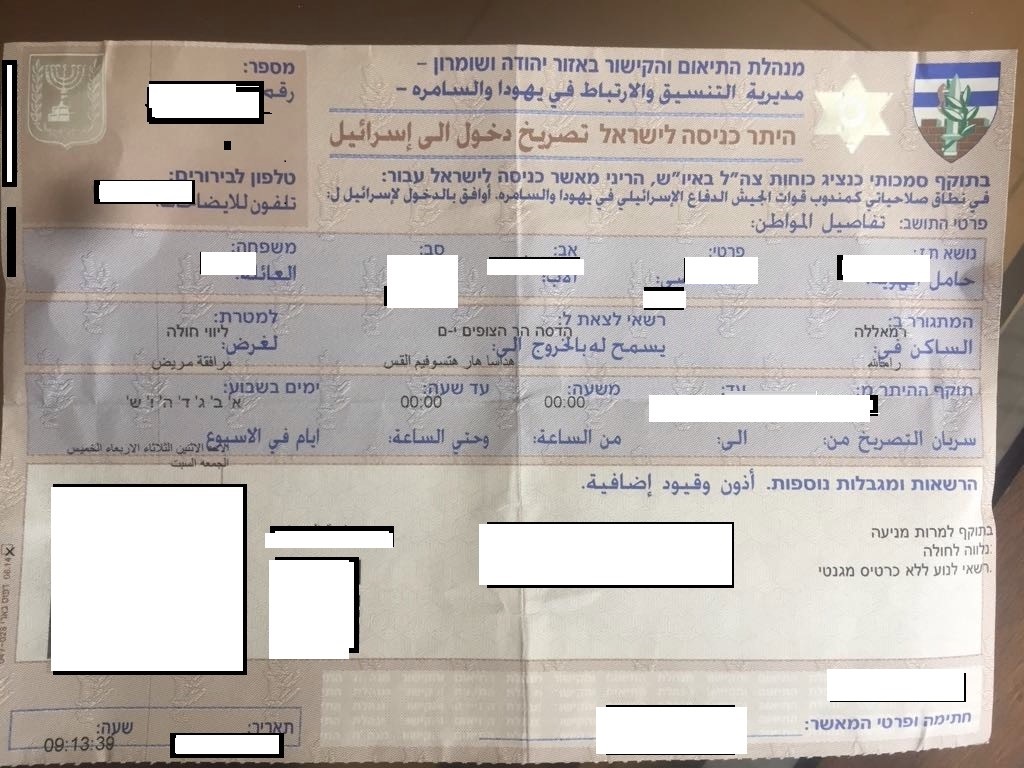

Even if Osama were to get an entry permit into Israel, how realistic would it be for us to move there based on temporary permits?

June 1, 2020

I requested the meeting with the insurance agent to open a pension fund, but he insisted on trying to sell me disability, life, and supplementary health insurance.

“Coverage for organ transplants, operations abroad and medical evacuation flights will cost you just 88 shekels ($25 U.S.) a month for the entire family.” His laptop screen had a table with the names of Osama, my partner, and our children, with an X next to each name.

“Delete my partner’s name,” I said. “You can’t insure him.”

“He’s not a citizen?”

“No.”

“How long have you been married?”

“Six years.”

“That’s strange. My cousin married a British guy, also not Jewish, but after two years I’m pretty sure he was at least a permanent resident.”

“It’s different for Palestinians,” I said.

“Are you sure? Sounds odd to me.”

“In 2003 they passed a law blocking family unification for Israeli citizens who marry Palestinians.”

“But usually you can bring a spouse to Israel.”

“Usually you can. Unless the spouse is Palestinian.”

He appeared skeptical but deleted the X next to Osama’s name and launched into an enthusiastic description of a pool in a hospital in Germany, where they infuse chemotherapy into the water in order to target the treatment to the area of the tumor and thus minimize damage to healthy cells.

“It doesn’t exist in Israel,” he said proudly, relishing my recovery from the cancer that, thank goodness, I have yet to be afflicted with.

I was having a day of meetings, in and around Jerusalem and Tel Aviv. After the Muslim holiday of Eid al Fitr, the daycare centers and kindergartens were allowed to reopen in Palestine and thus –parents could go back to work. In the morning, crossing through the Qalandia checkpoint on my way to Jerusalem, I realized how much we are living with the sense that the coronavirus has retreated. The soldier who checked my documents wore a face mask that had slipped down to her chin, and when she gave me back my ID card, her exposed fingers touched mine.

After the meeting with the insurance agent, I continued to the Ministry of Interior office in the Tel Aviv suburb of Holon. I went to the office of the deputy director, the one who had been decent with me during my first visit two years earlier, when I had come, Adam in the baby carrier strapped to my chest, to file an application for family unification – temporary permits that would allow Osama to enter Israel on the basis of a “humanitarian” exception. It turned out that deputy director had grown up on the same tiny street in Or Yehuda where my father grew up, he in the 1960’s and my father in the 1950’s. We talked about the street, which I knew well from visits to the dark and cluttered apartment where my grandmother continued to live until they put her in a nursing home. Maybe out of a sense of solidarity, the deputy director had given me hints about the justifications his superiors would employ to deny our application – thus allowing me to prepare counter-arguments. But on this second visit, his approach was more hostile.

“I don’t have any outstanding applications from two years ago,” he said, typing my ID number into the computer. He looked at the screen and then said: “Your application was rejected in 2014.”

“That was the first application. I submitted a second application in 2018, in which I addressed the denial of the first application.”

“Ah, yes,” he said. “I see it. But it’s not my file, it’s with Arnon.”

“As deputy director, it should concern you that an application has been outstanding for two years without receiving any kind of answer.”

“As deputy director, it should concern me that the application remain outstanding until it is fully processed, and that the clerk responsible continue his dedicated attention until the file is complete. Go talk to Arnon, it’s not my file.”

I waited outside Arnon’s office until the door opened.

“My name is Umm Forat, and I met with you two years ago, when I submitted an application for family unification.”

“Oh, yes, Dr. … Dr. …”

I was surprised that he apparently remembered us. “Fahed. Dr. Osama Fahed. Since then, I’ve been sending you reminders by email and registered mail, trying to get in touch by phone, and I haven’t gotten any response.”

“That’s right, I think I got something from you a few months ago. I passed it on.” He typed my ID number into the computer. A few minutes passed.

“I’ll check and get back to you.”

“Could you at least tell me at what phase the application is? It’s been two years.”

“There are all kinds of evaluations … I’m not sure how much I’m allowed to say. To tell you the truth, this is the only application that I have handled, for giving status to a Palestinian spouse. We don’t get a lot of these in this office.”

Outside, the sun had started to set. It was a pleasant day, almost hot. I missed balmy Tel Aviv evenings, without the coolness of the hills of Ramallah. I continued to a work meeting inside Tel Aviv, using Waze to circle around the traffic. Still, it took me ten minutes to drive the kilometer and a half from the northern end of Rothschild Boulevard to its southern end. Before I moved in with Osama in the Ramallah area, I had lived in south Tel Aviv, and I used to cross Rothschild Boulevard on morning runs or, later in the day, on rollerblades, enjoying the pleasant ride under the Ficus trees. I tried to imagine myself strolling along the boulevard with Osama, Forat and Adam, like the families I used to pass when I was still single. Forat and Adam would go nuts over the fountain at the end of the boulevard. Maybe I would buy them chocolate pizza at Max Brenner, the chocolate restaurant that I lived above for two years. If I were to tell Forat there’s a restaurant where she can order chocolate soup, she wouldn’t believe me.

Even if Osama were to get an entry permit into Israel, how realistic would it be for us to move to Tel Aviv based on temporary permits, that are renewed or are not renewed, that don’t allow him to get health insurance or drive a car, and that expose him to the hostility that people here express toward Palestinians?

I finished my last meeting. I didn’t hurry. The children would be asleep, anyway, by the time I got home. I watched young couples holding hands and turning down Ahad Ha’am Street to the Neve Tsedek neighborhood, maybe on their way to a walk along the sea or to celebrate the reopening of the bars. I felt a wave of longing, but I wasn’t sure for what. For Tel Aviv? For life before children? For a way of life with Osama that, I guess, will not come to be?

I decided to file an appeal in the Ministry of Interior’s administrative tribunal, if only to get a response to our application. I took comfort in the fact that Tel Aviv has become too expensive to raise children in, anyway.

This post was also published at haaretz.com on June 1, 2020: