On a morning run, I discovered that settlers took over a spring that Ein Qinya is known for, on lands belonging to a Palestinian family

Every time I return from time abroad, I notice the changing scenery in and around Ramallah. Some of the changes are natural: an apartment block at the edge of the street where a thicket of trees used to be. A new trendy coffee shop that replaced a different trendy coffee shop. The first falafel stand opening in a small village. But in the West Bank, changes in the scenery are also the result of a struggle between Israeli settlers and residents of Palestinian villages. The settlers try to take for themselves another bit of scenery, and the Palestinians try to fend them off. My love for long runs exposes me to these areas of transformation, where Palestinians perceive Israelis as a threat. In other words, they perceive me as a threat.

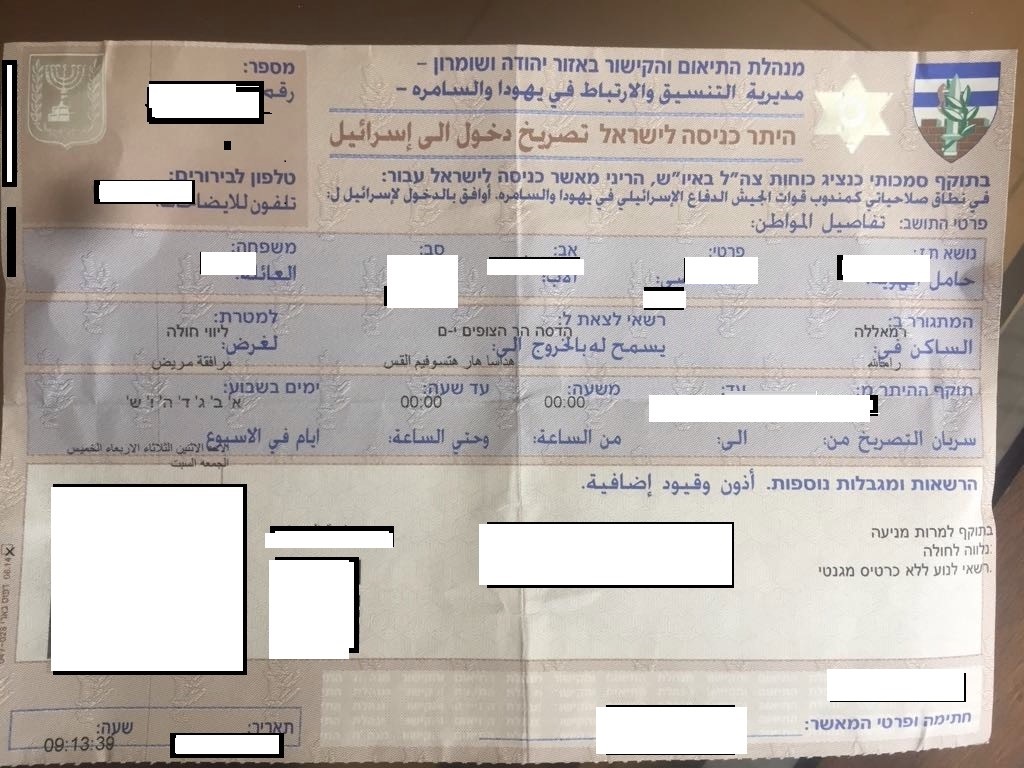

Inside Ramallah my situation is not that bad, because during the day one doesn’t expect to see Israelis. The army prefers to make arrests there at night. Villagers, on the other hand, feel the Israeli presence strongly: army patrols, flash checkpoints, harassment and attacks by settlers and in some places also commerce with settlers.

But in the villages I can run without getting run over by a car or choking from exhaust fumes, and so it’s hard to give up on trail running there. It’s rare to see a woman running. I wear loose-fitting pants and shower passers-by with smiles and greetings of “good morning” in Arabic, in the hope they won’t think I’m a settler. Their fears are a threat to me.

Two weeks after we returned from the United States, I set out for an early Friday morning run to Ein Qinya, a small, beautiful village, home to 750 residents, bordering Ramallah and hemmed in by the Israeli settlement of Dolev. I ran from the bourgeois neighborhood of Tireh down the road that leads to the wadi. On my left was a pretty stream in which mostly sewage flowed. On my right, olive trees dotted the slope of the hill, together with fig trees heavy with ripe fruit. Birds flitted between the trees, and a fox crossed the road. When I reached the village, a young man walked past me.

“Sbah el-khair,” I greeted him with a smiling good morning.

“Sbah el-nour,” he answered, with a closed face.

I passed the pink-walled elementary school, with the red flags of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine draping its courtyard wall. At the mosque I turned left, toward the path that leads out of the village. Quiet. A cluster of clouds above portended the approaching autumn. Osama and I liked to walk there in the winter, to pick the mallow that grew wild in the fields and to show Forat the donkey and chickens.

I dispatched another “good morning” to a ten-year old boy riding his bike. He accelerated, passed me with breakneck speed, trying to impress me or maybe – to alert his parents? I didn’t see anyone else outside.

I ran on a path that went down to the farmland, toward Wadi al-Major. Osama and I once met a young man there who complained that settlers from Dolev were trying to take one of the springs that Ein Qinya is known for, which, he said, was located on lands belonging to his family. I remembered from previous runs that the path ended well before the spring, disappearing into thorny bushes that in winter were dotted with wildflowers.

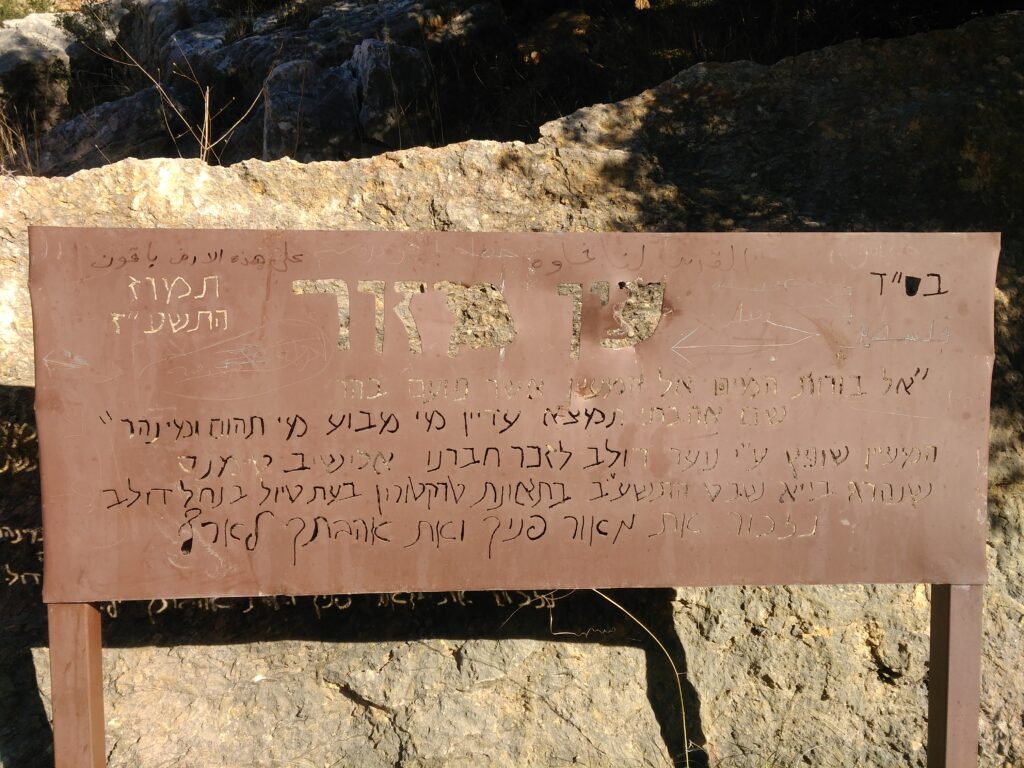

But the path appeared to continue and even widen alongside the wadi, as if it had been cleared. Suddenly I saw trail markings in the style of the Israeli Society for the Preservation of Nature – a green line painted on the rock, highlighted by two painted white lines. I ran another few dozen meters and reached a site containing a gazebo-like thatched roof, benches and a big sign that read, in Hebrew, “Ein Mazor”, a Hebraization of the original name, Ein al-Major.

The settlers from Dolev had taken over the spring. And for reasons I did not understand, they had also cleared and marked a trail from the spring to the village of Ein Qinya.

The sun climbed in the sky. Before me was the path that would lead to the settlement. Behind me was the path from which I came which, thanks to the clearing – now led from the settlement to the village. Maybe settlers would come now? I had seen them once on a Friday, on the road above. Families going on a hike had entered Ein Qinya, and the men carried guns.

I sprinted back the way I had come. I practiced the sentences I would need to say in Arabic. I also practiced the smile and the ease I would exude. I passed a donkey tied to the first house of the village. The boy on the bike made a ring around me.

“Where is your mother or father?” I asked him.

“At home.” He pointed to a two-story house at the edge of the village.

I knocked on the door of the apartment on the first floor.

“Who’s there?” A female voice.

“My name is Umm Forat,” I answered. If she would hear that I’m a woman, she wouldn’t need to put on her hijab.

A girl of about sixteen, hair uncovered, opened the door. She wiped her hands on a dish towel. “Yes?”

“Where is your mother or father?” I asked.

“My mother is sleeping, and my father took the goats out,” she said.

“OK, um, maybe you can tell them something for me?” My stutter was awful. “I live in Ramallah with my husband and children. I like running here. We were in the United States for a year. We came back now, and I saw what the settlers did, that they took the spring.” I gestured in the direction of the path. She nodded. “I want to tell you that if you see me here in the village, don’t be afraid. I live in Ramallah, I run here and then run home, nothing more …”

My nervousness and embarrassment turned the frozen smile I had plastered on my face to a real one. The girl’s smile was real, too. “OK,” she said.

I continued running toward the exit from the village. I didn’t see anyone else outside until I reached the end. Under a tree, next to the school, stood two young men. I approached them.

“Good morning,” I said, a huge smile on my face.

“Good morning,” one of them answered. He was about twenty years old.

“I want to tell you something,” I said. “I live in Ramallah and like running here. Um, I saw what the settlers did …” I pointed in the general direction of the spring. “If you see me here in the village, don’t be afraid, OK?”

One of the young men stared at me. The other said, “OK.”

“OK, bye,” I said and ran toward the road leading out of the village.

When I got home, the sun was high in the sky. My running watch recorded twenty kilometers. I sat next to the door of the apartment and took off my shoes. Adam and Forat jumped on top of me.

“Ima, Baba let me eat Irshalla!” Forat said, referring to the local biscuit that she had missed during our year in Philadelphia.

“That’s great,” I said. Adam pulled at my shirt, asking to nurse. I told Osama what had happened.

“Why do you need to run there?” he asked.

“Because it’s beautiful, quiet, and safe there,” I said. He raised an eyebrow at the word “safe”. I corrected myself: “I mean, there aren’t a lot of cars there.” I felt his disapproval, his criticism of me that I’m not cautious enough. But how exactly does he expect me to be cautious under our circumstances?

“What happened, Ima?” Forat asked, noticing the tension between us and maybe also my residual anxiety. How to explain to her what I was afraid of?

“In Ein Qinya, sweetheart, people took a spring. And I was afraid that the people in the village would think that I had taken it, and would be angry at me.”

“But did you take it?”

“No, sweetheart. People close to me took it.”

“So every time you run there, you’ll introduce yourself to everyone you meet?” Osama asked.

“No,” I said, and I smiled a smile intended to dissipate the tension between us and also to calm myself down. “I’ll stop introducing myself on the day when someone answers, ‘Oh, yes, I heard about you.’”

This post was also published at haaretz.com on January 31, 2020:

I had this article saved some time in the past but my computer crashed. I have since gotten a new one and it took me a while to come across this! I also really like the design though.

It’s hard to find well-informed people on this subject, but you seem

like you know what you’re talking about! Thanks

Thanks!